The Worst Argument to Descend Down .

The argument

In discussions I have participated in, I have noticed that people make slippery-slope arguments when they have no other good arguments to make. To provide an example, let’s look at two people who are debating methods of protecting local farmland from floods.

Person A: “We must build a dam on the river, or else our crops will be destroyed again and again.”

Person B: “We cannot build the dam, because this a slippery-slope until we build dams on all of our rivers and creeks, and this would be horrible! This would bankrupt our town and destroy all of our aquatic wildlife.”

Casual observers of this exchange may not see any error in Person B’s logic. Indeed, the idea of damming all waterways is a ridiculous one; however, in no way is this a valid rebuttal to Person A’s claim. To understand this, let’s use Oxford Languages to formally define the slippery-slope argument:

An idea or course of action which will lead to something unacceptable, wrong, or disastrous.

In the above scenario, the disastrous course of action is damming all waterways. Often, slippery-slope arguments will be framed as “if we do X, then the next thing will be Y,” where Y is a negative outcome. If the person making this is particularly indolent or vacuous, they will name the slippery-slope outright, as if it is a commonly accepted argument, on par with the Pigeonhole Principle or Axiom of Choice.

Why is the slippery-slope argument a fallacy (that is, an invalid argument)? Well, we can boil Person B’s argument down to the following:

- Suppose we dam the river

- ?

- Every river will end up dammed, thus we should not dam the first river

As one can see, there is a break in Person B’s argument where there is no logic — a “non-sequitur” — and non-sequiturs exist in every slippery-slope argument.

In short, the slippery-slope argument is not a valid argument because the person making it never explains how the first action leads to the end result; they assume that taking action A inevitably leads to terrible result Z. This is where the name “slippery-slope” comes from: taking a step will lead one to slip and fall down the slope. One may counter that, yes, that is the point of this argument; there are some slopes which are so wet that one must fall down; however, that is a fallacy! One is making a claim without evidence and asserting it as a fact.

This does not mean that we can never argue against some action A because it will lead to some outcome O. But be careful: provide evidence that O follows from A (or, some sequence of steps can follow from A to O).

I would like to contrast slippery-slope to a related, but logically valid, argument: induction.

Induction

Induction is a mathematical proof technique whereby one shows that some statement holds true for some starting point (“base case”), then shows that if the statement is true for some number n, then it must be true for n + 1. Thus, the statement is always true. If we were making a cookbook of mathematical proofs, the recipe for induction would be:

Gather a statement S(n) which is either true or false for a value n

- Show that S(n) holds for the base case (often n = 0)

- Show that S(n) ⟶ S(n+1)

- Thus, S(n) holds for all n

Step 2 is the most critical ingredient in this recipe, and is what the slippery-slope argument lacks.

A Side Note

Please never use the word “proof” outside of a mathematical context; in the real world, we can never say a piece of evidence shows that a particular claim to be true with a probability of 1. To do so would be too confident in our empirical findings. Even well-accepted conclusions, such as that the Earth is round, does not have “proof”; we just have very-strong evidence that points to this finding. As level-headed rationalists, we must admit that all of our data has a certain probability of being incorrect. (Note: I am not saying there is not an “objective truth”; I am saying we should be careful in our language and that there is always a possibility in our arguments being wrong.) So, for example, instead of saying “the increased cancer rates from smoking proves that tobacco smoke is a carcinogen,” say instead “the increased rates of cancer is strong evidence that tobacco is a carcinogen.”

Conclusion

If you are even making an argument, please do not use the “slippery-slope”; if you do, I will gleefully push you down it.

Exercises for the Reader

- Use induction to show that sum S of n integers is: S(n) = n(n + 1)/2

- Eradicate the scourge of the slippery-slope argument by forwarding this article to every person you know

- Cure all diseases

Recommended

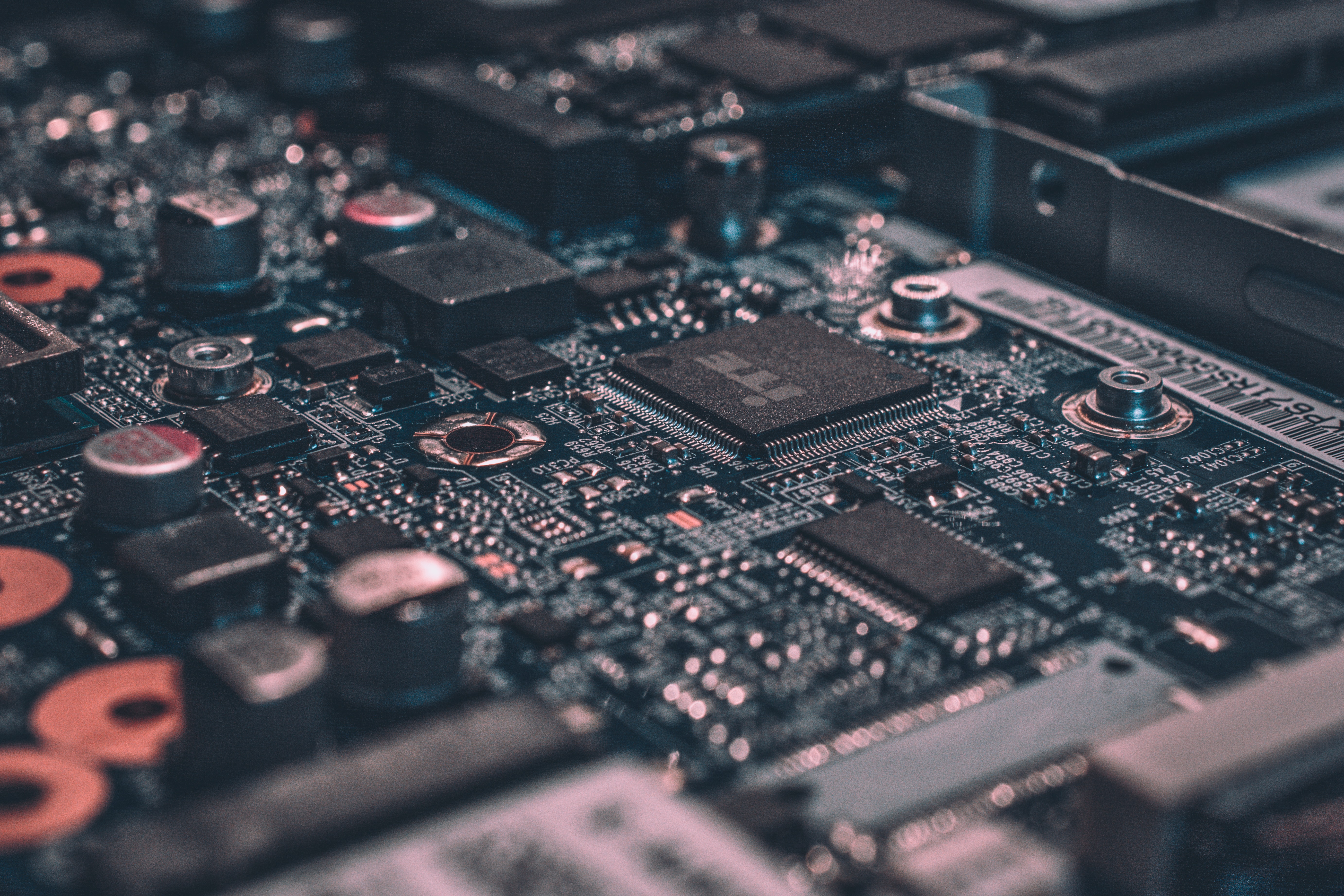

Innovation that turned out to be vaporware.

The Most Important Open Problem

A million-dollar equation.

Can a statement be true, and the converse of it also be true?